You might have seen Brian Hibbs’s annual analysis of the 2023 BookScan numbers over at The Beat a couple of weeks ago. Hibbs did his usual painstakingly thorough job grinding through all the categories and sales figures to dig out a few headlines, namely that Scholastic remains the leader by such a margin that you have to rescale the sales chart to see anyone else, and that DC Comics and Marvel Comics have simply vanished from the book market for all intents and purposes. There’s also another story about the market for adult (e.g., not younger reader) graphic novels being driven much more by back catalog than by frontlist.

All these trends raise a couple of questions, considering the importance of the bookstore channel to the overall health of comics publishing.

Does Scholastic’s success help anyone but Scholastic? The first thing that jumps off the spreadsheet is how complete Scholastic’s domination of the marketplace has become. The company owns the top nine slots and 16 of the Top 20, driven by the maniacal force of kid-lit that is Dav Pilkey, according to Hibbs’s chart (which does not include the graphic novel-ish “edge case” of Jeff Kinney’s Wimpy Kid franchise, from Abrams).

This is, of course, awesome news for the Scholastic Graphix imprint, which continues to develop new authors and franchises like Scott Cawthon’s Five Nights at Freddy’s; for parents who want to get their little ones reading and occupied; and for Pilkey himself. I imagine it’s also good if you own a bookstore that can turn that kind of volume and traffic into add-on sales or cross-selling to parents and older siblings.

But more than 15 years into the Scholastic-led explosion of young reader graphic novels, it’s worth asking if this is doing the wider industry or even the medium of comics much good. It’s certainly not awesome for other publishers angling for younger readers, who are getting ground into paste by Scholastic’s total market domination. But more fundamentally, we seem to have come full circle from “comics aren’t just for kids anymore!” to “comics seem to be just for grown-ups now” to “is anyone but kids buying graphic novels in big numbers?”

There’s been a lot written about the differences in generational audiences for comics, including some by me, but one thing that has received less attention is the impression left on kids as they age up. For many in my (GenX) cohort, and for the Boomers before us raised on ECs or Marvel Silver Age material, some comics stories seemed slightly more sophisticated than average kid-lit, especially ones that required some awareness of the wider world. It was a rite of passage to progress from Archie and Richie Rich to Detective Comics and X-Men.

By feeding the endless appetite of preschoolers and elementary school kids with material that is wonderfully, proudly, unabashedly juvenile, have current kid-oriented graphic novels cemented the medium itself as an artifact of early youth, something to be left behind at a certain point in development?

Certainly there is no clear path from Dog Man to almost anything sold periodically in the Direct Market, despite plenty of hopes and efforts spent attempting to build those bridges. There was never any guarantee how many of those readers would carry over, but after this long, it seems increasingly clear that the number is not that much greater than the number of kids who develop into lifelong DM customers through any other onramp.

Have the Big Two given up on the trade book market? One of the most disappointing tidbits in the sales charts is the complete disappearance of DC and Marvel, which together account for under 10% of the total non-manga book market in 2023. Hibbs has a pretty complete discussion of this in his write-up, but there’s one observation I would add.

Collecting story arcs as trade books used to represent a reasonable way for publishers (and creators) to recoup the costs of ongoing and limited series that went into a sales decay after the first issue. The predictability of these moves may have hurt in the medium-term by inculcating a “wait for the trade” mentality among readers, but in the long run, having these stories in print and widely available was a selling point.

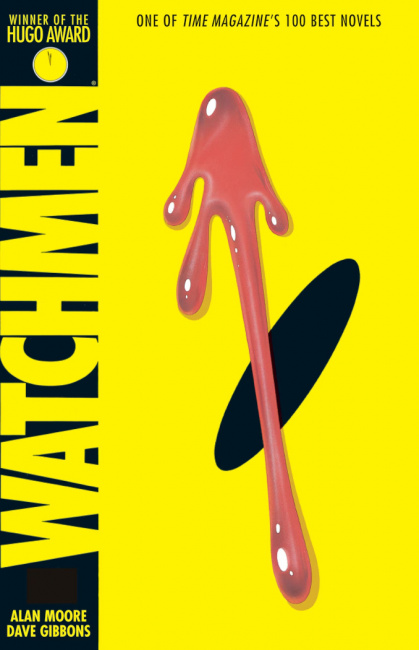

To the extent this remains part of the game plan, it appears to be so DM-centric as to make current or recent trades practically invisible outside of comic shops. Nearly all the sales are dominated by the perennial backlist best-sellers from decades past like Watchmen, Dark Knight and Sandman. Marvel, as Hibbs notes, is a complete no-show, outdone by its licensing partners.

DC and Marvel may have some other things on their mind these days, but it feels like malpractice when the companies manage to do an even worse job than ever coordinating with media events, as when Vertigo’s Bodies trade was nowhere to be seen when the series dropped on Netflix in October, and books did not do much to support DC’s (bad) movies during the fall. Would it have helped to have those books in bookstores? I guess we’ll never know. Will Marvel have a decent trade bookstore program in support of Deadpool & Wolverine? I’ll take the “under” on that bet.

How solid is the post-March literary graphic novel market? Hard to believe that it is more than ten years since the first volume of the March trilogy first appeared, back in 2013. At the time, and in the decade since, having the memoir of one of the most celebrated and consequential figures in recent American history available in comics format did wonders for both the stature of literary graphic novels and for the business. The sales on each volume of the trilogy were larger than just about any other literary graphic novel before or since, and the series remains a perennial strong seller even in back catalog.

In that, March benefited from three factors that are hard to repeat. First is that John Lewis lent his stature to the project, bringing a combination of historical gravity, charisma and current-day newsmaking ability that is hard to match. Second, though the book deals with serious subject matter in a rigorous, historically-accurate way, it is also accessible to younger readers, making it a cross-category threat that works in both the adult and teen/educational markets. And finally, many of the issues of the Civil Rights era have become newly relevant in American politics, particularly during the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020.

That said, the only book that has come close to this kind of enduring, six- and seven-figure sales market popularity is They Called Us Enemy, also from Top Shelf Productions, which also benefited from celebrity author George Takei and an all-ages approach.

Without these titles leading the way, how much of a serious literary graphic novel market is there in North America right now, notwithstanding the efforts of great publishers like Fantagraphics Books, Drawn & Quarterly, Abrams and the like? Is this, barring the occasional breakout hit, always going to be fundamentally a small-press play? Meanwhile, the supply of these kinds of books, often in beautifully-designed editions, continues to increase, along with the storytelling ambitions of next-generation creators, some of whom are now pouring forth from graphic novel MFA programs.

Will 2024 be one for the books? Over the last decade, we’ve seen the balance of power shift from the DM to the bookstore, largely on the back of manga (largely VIZ Media) and Scholastic. But like so much else in the world right now, the rising tide needs to raise at least a few more boats.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.

Rob Salkowitz is the author of Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture and an Eisner-Award nominee.

Source: ICV2