Trina Robbins grew up loving comics but came of age at a time when comics for girls and women had disappeared and the industry was dominated by men. She helped transform the medium by creating her own comics, publishing and mentoring other women cartoonists, and documenting the history of the women who had always been a part of the industry but were seldom mentioned in the standard texts.

Robbins was born in Brooklyn in 1938, the daughter of Jewish immigrants from Belarus (then part of Russia). She read and drew comics from a young age, and from the beginning she gravitated toward female characters: Brenda Starr, Millie the Model, and Katy Keene, the multitalented model created by Bill Woggon for Archie Comics. Katy Keene comics included both paper dolls and clothing designs submitted by readers, and Robbins created her own paper dolls as well as making her own comics. In her teens and early 20s, Robbins moved away from comics, turning her talents toward fashion design; she sold her handmade dresses at craft fairs, ran a boutique in New York called Broccoli, and hung out with models and rock stars. In 1969 she designed the costume and hairstyle for Vampirella, the title character of Warren Publishing’s black-and-white horror magazine (a companion to Creepy and Eerie).

It was the New York alternative paper the East Village Other that got her back into making comics. The comics published there were radically different from those of her youth, and Robbins saw new possibilities there. The Other published her first comic strip, which was submitted on a whim, and then continued to publish her work regularly. She moved to San Francisco in 1970, as the Underground Comix scene was just getting started, working at the feminist paper It Ain’t Me, Babe.

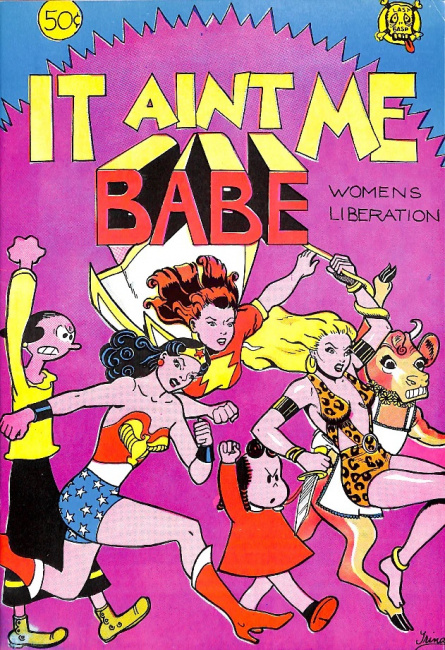

In 1970, Robbins teamed up with Barbara “Willy” Mendes to produce It Ain’t Me Babe Comix, a 36-page anthology that included work by Robbins, Mendes, Nancy Kalish, Carole Kalish, Lisa Lyons, Meredith Kurtzman, and Michele Brand; it is the first comic that is known to have an all-female creative roster. The comic was published by Last Gasp and went through three printings for a total of 40,000 copies. With that proof of concept, Last Gasp publisher Ron Turner encouraged two of his staffers, Patricia Moodian and Terre Richards, to start an all-women comic as an ongoing concern. Wimmen’s Comix launched in 1972 and provided not only a place for women cartoonists to publish but a model for them to do so; Robbins was both contributor and one of the roster of editors who took turns with each issue. The comic became the centerpiece of the Wimmen’s Comix Collective, which fostered female creators, and it was also the model for women’s comics that followed, including Twisted Sisters, by Diane Noomin and Aline Kominsky-Crumb, who were originally members of the group but broke off because of creative and personal differences (see “R.I.P. Aline Kominsky-Crumb”).

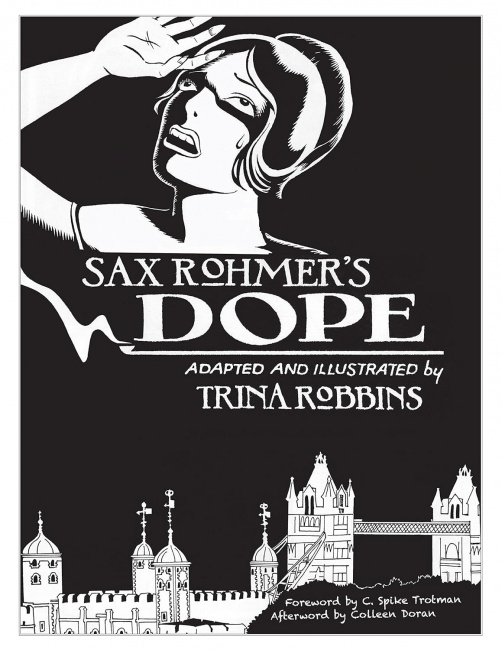

Robbins’ interests led her far beyond the world of the undergrounds, however. In 1981-83 she adapted Sax Rohmer’s Dope into comics for Eclipse Magazine, and in 1985 Crown Books published her graphic adaptation of Tanith Lee’s contemporary novel The Silver Metal Lover. Both were republished over 30 years later by the late Drew Ford’s It’s Alive imprint (see “‘The Silver Metal Lover’”).

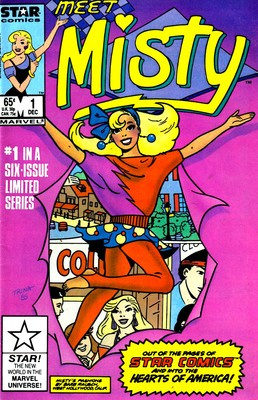

Robbins’ next project was Misty, a limited series for Marvel Comics’ Star imprint, which was aimed at young readers. The comic was an updated version of Katy Keene for modern readers, with a heroine who was a soap opera actress and who appeared on the last page of the first issue wearing a barrel and asking readers to send in their clothing designs. Misty only lasted six issues, from 1985 to 1986; readers loved it (judging from the enthusiastic fan mail) but had a hard time finding it at a time when comics had moved into the male-dominated direct market. “In those days if you wanted to buy a comic, you had to go into a comic book store which was wall to wall boys and they didn’t want to carry anything for girls,” she told Alex Dueben in an interview at The Beat. “Though I used to get manilla envelopes stuffed with letters from girls who loved Misty. They said I love your comic but I have such a hard time finding it.” She then created California Girls for Eclipse Comics, a similar series that ran for eight issues from 1987-88, but it failed for the same reason: Comic shops wouldn’t stock it.

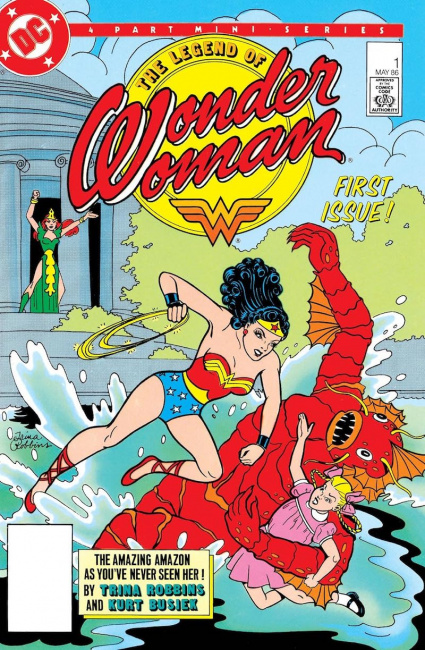

In 1986 Robbins also drew a four-issue Wonder Woman miniseries, The Legend of Wonder Woman, written by Kurt Busiek. Robbins made another stab at comics for girls in 2000 when she created the superhero comic Go Girl! The comics, which were initially published by Image but moved to Dark Horse after five issues, were written by Robbins with art by Anne Timmons.

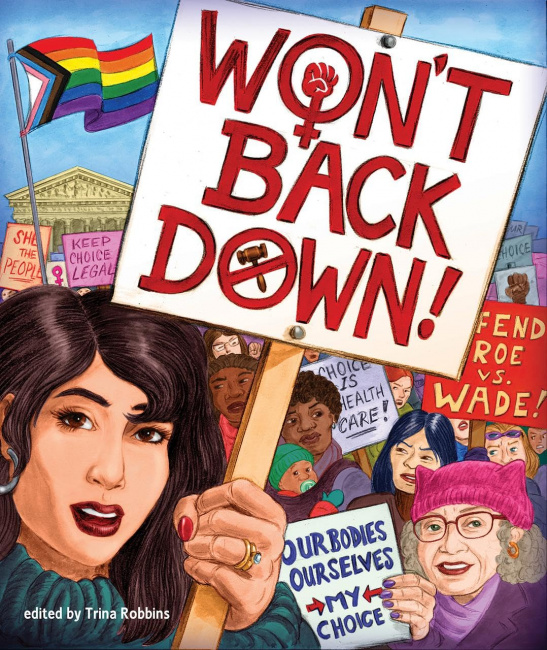

However, the late 1980s were a rough time for Robbins; the undergrounds had waned, and she was never a good fit with them anyway; at the same time, she hadn’t found her place among the new publishers and creators who were coming to the fore. “I felt that I was over the hill,” she told Dueben. “It got to the point where when I attempted to draw, I couldn’t. I just got really depressed and had anxiety and so I just stopped. I couldn’t do it.” Although she dropped drawing, she continued writing and editing, and in 1990 she edited and published Choices, a pro-choice benefit anthology for the National Organization for Women, which brought together work by a wide range of male and female artists from the undergrounds, comic strips, and superhero comics; over the years she would edit and contribute to a number of such anthologies, including the 2023 Won’t Back Down!, a reaction to the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision (see “Trina Robbins Helms Pro-Choice Anthology with Over 30 Creators”).

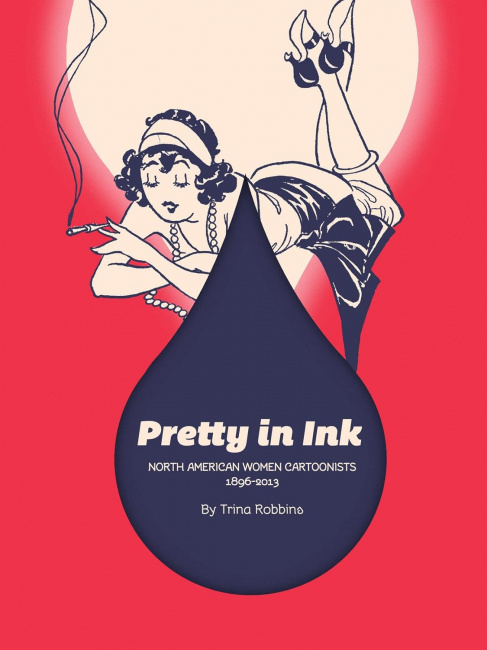

She also found a whole new direction for her energies, documenting the often-forgotten history of women comics creators. She started out by collaborating with Cat Yronwode on Women and the Comics, published in 1985 by Eclipse, and went on to write A Century of Women Cartoonists and The Great Women Superheroes, published by Kitchen Sink in 1993 and 1997, respectively; From Girls to Grrrlz: A History of Women’s Comics from Teens to Zines, published by Chronicle in 1999; and The Great Women Cartoonists, published by Watson-Guptill in 2001. More recently, Fantagraphics has published her Pretty In Ink: North American Women Cartoonists 1896-2010 (2013), The Flapper Queens: Women Cartoonists of the Jazz Age (2020), and Dauntless Dames: High-Heeled Heroes of the Comic Strips (2023). Hermes Press has also published a number of her books, including Babes in Arms: Women in the Comics During World War II (2017) and Gladys Parker: A Life in Comics, a Passion for Fashion (2022).

Robbins was also one of the co-founders of Friends of Lulu, a dedicated to promoting women cartoonists, encouraging publishers to create comics for females and retailers to sell them, and preserving the history of women in comics. The organization, which was formed in 1994 and closed its doors in 2011, was a prominent presence at comics conventions and published a guide for retailers on how to bring more women into their stores (see “Torsten Adair of Barnes & Noble”); they also sponsored the Lulu Awards and the Women Cartoonists Hall of Fame.

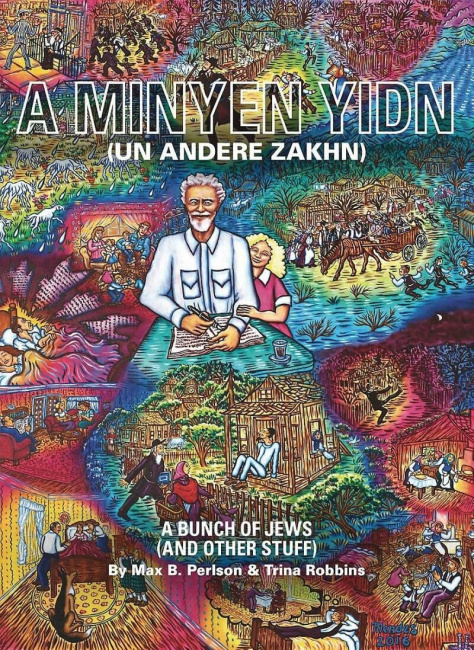

Continuing to practice what she preached, Robbins wrote many comics for female audiences, and she brought comics and history together with the 2011 publication of Lily Renée, Escape Artist: From Holocaust Survivor to Comic Book Pioneer, a middle-grade graphic novel published by Graphic Universe that brought new prominence to the longtime comics artist (see “R.I.P. Lily Renee Phillips”). She also wrote the 2017 A Bunch of Jews (and other stuff): A Minyen Yidn, a graphic adaptation of a collection of short stories by her father, which had been published in Yiddish in 1938.

In 2002, Robbins responded to an ICv2 column on comics for children, saying, “Brian Hibbs wrote about how stores won’t carry kid-friendly titles, and you put the responsibility for producing these comics on women. I say it’s the responsibility of all of us: publishers and editors, retailers, and comics writers and artists. The editors have to give our kid-friendly comics a chance, and the retailers have to stock them. Only by working together can all of us add much-needed diversity to the comics industry, and maybe save it from going under” (see “Trina Robbins on Comics for Girls”).

That is in fact what happened, and in large part, it happened because of Trina Robbins, who devoted her life to creating, editing, and promoting comics for girls and for women, and who left her industry in a much better place than she found it.

Source: ICV2