Nick Landau is one of the co-founders, together with Mike Lake and Mike Luckman, of the comic store chain Forbidden Planet, and he also co-founded Titan Distributors, which was sold to Diamond in 1993 and became Diamond UK. Landau and his wife, Vivian Cheung, now own Titan Entertainment Group, which includes a publishing company and nine Forbidden Planet stores in the UK.

For ICv2’s Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary celebration, former retailer and DC Senior Vice President—Sales and Marketing Bob Wayne (see “ICv2 Interview: Bob Wayne“) talks to Landau about his years in the business. In Part 1, Landau talks about starting the Comics Media fanzine and his own distribution company. Part 2 covers his time at the publisher IPC, where he edited 2000AD, and the opening of the first Forbidden Planet store in 1978. And in Part 3, Landau discusses the shift to graphic novels, the sale of the distribution company to Diamond and the formation of the current company, as well as his part in the stage production of Thunderbolts: FAB.

This interview was conducted as part of ICv2’s Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary celebration; for more, see “Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary.”

To watch a video of this interview, see “ICv2 Video Interview – Nick Landau, Part 1.”

Bob Wayne: I’m here with Nick Landau, who continues to have one of the most unique careers in the comics business. We’re going to talk about his history and in particular how it relates to the growth of the Direct Market, both in the US and in the UK.

Nick, where and when did you first discover American comics and British comics?

Nick Landau: I guess we’re going to go back to the Nick origin story. It starts in the late ’50s. My father was an architect. My mother was an artist, a cartographer, and a sculptress.

After the war, London wasn’t in great shape, you know, a lot of it bombed out, and they decided that they wanted to move to America, so they took me as a small child over to the States. I lived in the States for about five years. That did actually give me an opportunity to have my first comic bought for me by my mother, who was very much encouraging me in all of these things.

I remember her giving me a Superman family book (I think it was a Jimmy Olsen, in fact, probably around ’57, ’58), and not thinking very much of it. That could have been the end of it all.

In ’60, we went back to Britain, and we gave it another crack with British comics. My grandparents, at that stage, decided that I should really partake in two British comics called The Beano and The Dandy, which were published by DC Thomson, which was a renowned Scottish newspaper publisher, but also happened to publish the sort of comics that all kids had been bought by their grandparents.

Again, I was really disappointed. That, as I’ve said, could have been the end of my comics buying career, except that a few months later, I came across an early 1960s import of Batman comics. Not sure precisely which one it was, but it was really from that moment I was hooked. Britain had actually not been getting any American comics until September 1959. Luckily, I was in the States before then, so I could have been collecting then. Anyway. So the comics themselves were really started. The first comic I bought myself was an early issue of Spider‑Man and an early issue of Fantastic Four. That was really the start for me of buying comics.

How long did it take before you went from buying comics and collecting comics to trading comics, selling comics, and becoming an entrepreneur at a young age?

What happened was my father had taken on a job at the University of Pennsylvania and became the dean for a semester a year in the School of Architecture. I spent three months a year from the early 60s in the States. We lived in Philadelphia on Sansom Street. The comics bug had caught me by then, and I would travel around Philadelphia, usually places like North and South Station, to pick up comics.

I happened to hear through the grapevine that because of the erratic distribution of comics in England, that there were certainly issues, I think it was Amazing Spider‑Man #18 and #19 and Fantastic Four #32 and #33, which I think were November around… What would it be? Not quite sure of the year [it was 1963—Ed.], but they were those issues, anyway. I picked up extra copies because I knew that friends would actually want them. I went back to England and I started selling them to friends who had missed out those because they couldn’t pick them up on the newsstands in the UK. In essence, selling to friends was the beginning of it. I think I was still at primary school at the time.

It wasn’t really until I got to secondary school that my buying and selling took off. I met with Derek Stokes, who ran a store later on called Dark They Were and Golden Eyed. We used to trade extensively. I would just buy and sell comics for the next few years through secondary school.

Then at some point, you got the bug to do your own fanzine and do an interview and news publication.

Yes. Comic Media was the publication. Comic Media came about in 1970. I had a good friend in Philadelphia who produced a magazine, and I thought, “This would be something that would be kind of cool to try and do.” I came back to the UK. It was on one of the semester trips that I would join my father in the States. When I came back to England, I thought, “Well, I really have to sort of give it a go, see if I can actually produce my own magazine.”

I produced this very first issue of Comic Media, which was a ditto printed copy, very crude‑looking, which had just a few articles on comics. I think the print run was 300 copies. Sold it at the ICA [Institute of Contemporary Arts]. Started actually distributing it around London to see if anybody would buy it. Didn’t have a huge amount of success. And then realized that the world had moved on and that I should be going to offset litho, and I started publishing Comic Media on a much more regular basis.

Several things happened. One was that I met up with Peter O’Donnell, who created a newspaper strip called Modesty Blaise that I’d greatly admired that used to appear in the Evening Standard, which was one of our evening papers. Went up to see Peter. By that time, I was working with a partner called Richard Burton as well, who was my co‑conspirator on Comic Media. Peter allowed me to run Modesty Blaise for free. I said, “I’d like to run this in my magazine,” because quite literally, here was a comic strip publication with no comic strip. It just had articles in. So Modesty Blaise became the very first thing that we ran in later issues of Comic Media.

Then on one of my trips to the States, which would have again been in the early 70s, I met up with Will Eisner. I’d been a big fan of The Spirit for quite some time. I used to have a copy of the 60s Harvey reprint of The Spirit stories, which was a beautiful publication. Also, in Italy there’s a magazine called linus. They used to run a lot of black and white comics, The Spirit being one of them, and of course, The Spirit looks fantastic in black and white. So I became a huge fan of a comic strip I couldn’t read because I couldn’t read Italian, but absolutely determined to find this creator, Will Eisner, who’d actually been producing it.

[I] found him in, I think it was, in New York in Park Avenue. At the time, he was producing a magazine for the army called PS Magazine. I went up to Will, and I said, “Hey,” hoping to repeat the same thing I’d done with Peter O’Donnell, saying, “Hey, I’d love to run The Spirit in my magazine.” He said to me, “Oh, how much are you going to pay me?” I said, “What do you mean? I thought you could just take the material and run it.” At that moment, he gave me my first lesson in creator rights. Here was kid publisher Nick being taught that actually, you had to pay for the material.

I remember what seemed at the time an outrageous amount of money. I paid him $50 to run the very first Spirit story that I’d run in Comic Media and bought about three or four issues worth at the time. Latterly, Will became, I guess, a mentor of mine. As we progressed through publishing and distribution and retail and all those things, and whenever he came over to England, we’d get together and he would express a huge interest in things that were well beyond what you’d expect an artist or a writer to be interested in. He would advise on all these other aspects of the business. We’d sit down and we’d talk, and we’d go through things.

So Comic Media became the flagship magazine. Latterly, we started an offshoot of Comic Media, that was Richard and myself, Richard Burton, called Comic Media News, which then became an offshoot publication in its own right, which Richard later then took over and published for many years.

Then we had a third publication called Comic Catalog, which was basically a buying and selling magazine, which ran for about five or six issues.

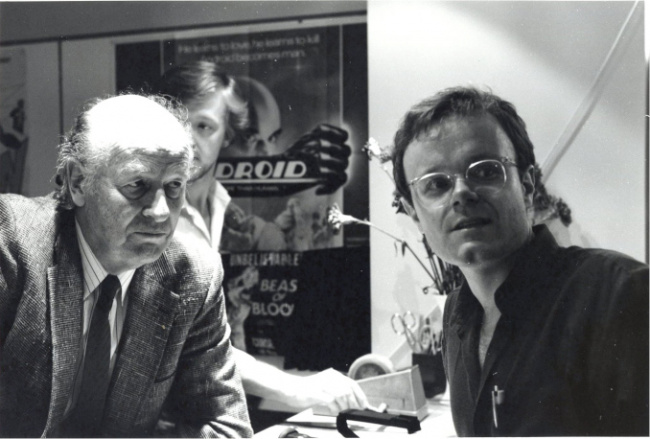

Image: Photo © Richard Burton

Mike Lake, Landau, Neal Adams, and Mike Luckman at the famous ten-hour signing by Adams, 1979.

Does this overlap with when you started wanting to set up the Comic Marts and organizing a convention? Were you doing this at the same time as the Comic Media work?

Yes, indeed. Comic Media came in 1970. The first convention I actually attended was in 1968, which was the first British Comic Convention, which was organized by Phil Clarke. Every year somebody different, a bit like the old science fiction conventions. You’d have a different team organizing the next year of convention.

By ’72, I figured it was my turn to actually run a convention. At the Waverly Hotel in London I organized the 1972 Comic Con, along with effectively the Comic Media team as it was, and brought a lot of animators along to the show.

What was happening was that we would have the same comic book artists, like Frank Bellamy, occasionally Frank Hamson, coming to the shows, and I thought, “I think it’s time to try something a little bit different.” Because I’d been very interested in animation, I brought in people like Richard Williams.

Then, thinking, “Who else is new and exciting in the animation field?”, I found Terry Gilliam. Terry Gilliam became the main guest star of Comic Con ’72. There were only three or four of us who were really running the thing. I was running the panel between Terry and the head of Halas and Batchelor who made Animal Farm.

I remember sitting between the two of them, and Terry Gilliam was this lovely chap, but very excitable and absolutely willing to defend to the hilt limited animation. John Halas, who was the head of Halas and Batchelor, sitting on the other side of me, was discussing how full animation was the way forward. Suddenly, this huge argument happened between the two of them, and I was caught. I felt a bit like [I was] caught between Homer Simpson and Bart Simpson, with one trying to strangle the other, in front of an audience of kids who had come just to watch two people talk about animation rather than try to strangle each other. It was an interesting event.

Another thing that happened at the show was that we had a cartoonist called Edweird. I think he was called Edward Barker, but Edweird was his name. Halfway through the show, one of the hotel managers came and asked me to come up to the lobby. A cartoonist had drawn a comic strip all over the walls of the lobby. I looked at that and I was absolutely devastated because I thought I was going to have to pay for the redecoration of the hotel, [laughs] which would have been a little problematic for me then. He said, “Who did this?” I looked around the cartoon and it was signed on the last strip as the cartoonist would always sign it. It just said, “Edweird.” I remember finding him in the show and saying, “Why did you do this?” He said, “I didn’t do it,” “But you signed it in the hotel lobby. You signed your strip.” He said, “Oh, God,” he said, “Must have had a bad night.” Anyway, I very luckily got out of paying the lobby bill because they said they were going to redecorate the lobby. They must have taken pity on me at the time.

I decided after that, that my convention career organizing was over because it was quite stressful. As it turned out, it wasn’t quite over, because in ’73, another convention was going to be organized, and it fell apart at the last minute. Myself and another guy had to, with a week’s notice, put on the 1973 convention as well. That was one of my first experiences with crisis management.

Also at the same time, out of the ’72 convention, I decided that the buying and selling of comics in the stalls was a far easier activity than running actual conventions. I set up the Comic Marts. The Comic Marts were basically just trading stalls. We started out at the first show in ’72 with about 20 or 30 stalls and ran them through to 1977 by which time we had about 250 stalls and a much larger venue, and it was much easier to run than a convention.

I certainly concur with that for my one time being part of running a convention. I swore that I would never do it again to myself, and I did not get into a subsequent one the next year.

With Comic Media, you were selling these to other people and probably selling them at the Comic Marts and such, is that when you developed your distribution service for Comic Media, was out of that?

Yeah. That again, would have been the early ’70s. I think we’re really talking ’71, ’72 here. I’d been buying and trading with the U.S. Because I used to go over to the States every year, I met up with quite a few people. One of those people became a long‑life friend, Paul Levitz (see “ICv2 Interview: Paul Levitz“).

At the time he was running The Comic Reader, which I think he’d taken over from someone else, from a previous publisher, and running it very successfully. We actually tied up with Paul and started serializing some of his features from Comic Reader into Comic Media News.

At the same time [I] met with Phil Seuling and Bud Plant, who I believe you interviewed earlier this year (see “Bud Plant Was There at the Start“). Bud was the big West Coast distributor, and Phil was buying and trading as well as running the New York conventions. I would attend his New York conventions and I ended up selling Comic Media through them.

The distribution of Comic Media, as the magazine became more professional, we went from an early print run, as I said earlier, of about 300 copies through to, I think the last issue of Comic Media, which was issue 11, we sold 10,000 copies worldwide. In essence, that was the beginning of the distribution system. It was basically trading fanzines.

Then I used to buy fanzines in from America, like The Menomonee Falls Gazette and Comic Reader again. I was then establishing a network of customers in the UK, of comic stores, and actually, non‑comic stores that I managed to persuade to buy comic magazines. Then I set up the Comic Media Distribution Service, so took the name of Comic Media, added distribution service.

On one of my trips to the States, which was ’72, I came across the Grand Street Book Center and discovered there was actually a way of not just distributing fanzines, but buying and selling regular American comic books.

I started an importation service in ’72, buying comic books from Henry Keller, who was the proprietor at the Grant Street Book Center. Somewhat ironically, I was importing comics before the Direct Market started in ’73.

I was also talking extensively with Phil. Phil Seuling had said, “I’m going to be setting up this non‑returnable network.” It seemed to be going on for a very long time, these discussions with Marvel and DC. I think they must have gone on for well over a year. I was very keen to get on board with this. I remember that Bud Plant and I were both slightly egging him on to say, “When is this going to start? When are you actually going to start being able to supply Marvel and DC Comics?” Then in ’73, the dam broke. He got his deal with Marvel first, and then DC afterwards. I became Phil’s first international customer.

Phil himself was an amazing character, a larger than life Brooklyn school teacher with a bear hug that could crush. He went from being an imposing character to one of the kindest, gentlest guys. Every time we used to come over to New York, he would just put a whole pile of us up. We’d grab our sleeping bags. There would usually be about 10 or 15 of us lying in sleeping bags on his floor before one of his conventions. He was incredibly generous.

His partner, Jonni Levas, I should mention at this stage, Jonni was a wonderful organizer. Very, very astute lady who I think helped Phil with a lot of the structure of the distribution. They were really true partners in the Sea Gate distribution business, which they formed.

No argument from me on that. Does this overlap with the same time when you had been doing film societies, television studies, and university, leading to film school? You’re doing all this simultaneously?

Yes, I’m afraid so.

Was that a good idea?

It was actually pretty rubbish idea in retrospect. I don’t know. I have this can’t sit still gene in me, which you may have noticed, as during the interview, I’m bobbing up and down a bit.

In, I think it was ’72, I had to give Comic Media a bit of a break because I went to Warwick University to study management science and immediately spent my first year working on the university newspaper, literally, before I did anything else. I spent the first year on the newspaper.

Then I discovered a film society, which had been losing a lot of money, and had been showing movies on a Wednesday evening, what you’d call the Italian slot, Pasolini movies, stuff like that. The whole audience consisted of the three members of the committee, of the film society committee, and that was it, no one else was going. I actually started attending those screenings and I realized, “Well, there is actually one person in the audience, and that’s me.” They were about to leave the next year, which would have been my second year. They said, “Would you like to take it over because you’re the only person here?” [laughs]

I duly took it over and changed it slightly. I started running screenings seven days a week. I had all-night screenings on a Friday, usually four movies. I understood that Warwick had the largest stay‑on-campus student body in the whole of the UK, which meant that I basically had a captive audience. The potential for the film society was really good. I had screenings over the weekend, Saturday, Sunday. Always the big movie was on a Monday. I think I gave people the day off on the Tuesday. Then I kept the Pasolini slot on the Wednesday, in deference to the previous year. Quite literally, it was a screening every night. I think we ended up with 40 people working for the society. Every screening was absolutely full. Ran that for two years. Ran that in ’73, ’74, my second and third years at university.

In my third year at university at the beginning of term, I came across a film studio and I thought, “Hey, this would be fun to start making movies.” I started borrowing all the audio‑visual equipment, and I went out and I started making films around the campus and then thought, “Everyone needs to be able to see these films.” In actual fact, nobody should have seen them, but that was just a little bit of ego on my part, I guess, making these things and then realizing that nobody was actually going to see them. So I set up a TV network around all the student halls, so that I could broadcast from the audio‑visual center, to all their halls of residence. Whether anybody actually ever turned on the TV, I don’t know. I hope they didn’t in some ways.

I realized that I couldn’t really do this by myself, so I brought on a team of other students to start making movies. I sort of, I suppose in some ways, became a producer rather than a director of films, and just built this. We did things like documentaries on the Arts Festival that happened every year in addition to making our own movies and our own TV. Then when I had a bit of spare time, I would go back and run the film society, and then there was this other thing called the management science degree which I was also attempting to do at the same time.

I managed to in my last year make a film, which ended up being a good portion of my degree; otherwise I probably would have been kicked out of the university. Instead of writing a paper, which I think you’re supposed to use to get most of your course points, I said, “I haven’t got time to write a paper for the management science degree, but I’ve made you a film instead.”

They had no idea how to judge it, but eventually I came up with some people to help them judge it, and it worked. That became my passport to film school. I was able to use my degree movie to then move on to film school the following year.

Then I spent about a year and a half at Film and TV school. The idea at the time was to go to…, probably end up at the BBC or somewhere like that being a director or producer or whatever. I spent about nine months working in television and about another nine months working in movies.

One of the things I did do, which was fun, was I made a movie called Six Inch Nails and Baling String, which was about the death of a circus. I went and joined a circus for about eight weeks, and just filmed everybody while I was there. Because it was such a small circus, I ended up being one of the performers as well. [laughs]

That took me a bit away from London, where I was still running the distribution service, and Warwick, where I was running the film society and the television society. I was doing possibly a few too many things at the same time.

Click here for Part 2.

Source: ICV2