Back in the go-go 80s and 90s, one of the most massive movers of the direct market was a 14-store juggernaut that sold millions of dollars in comics, was a broad-based hobby game store, and sold tens of millions of dollars in sports cards.

Then a new owner got busted on a variety of drug and weapons charges, and the chain went through a very public humiliation and twist in the wind until it finally, mercifully, died.

So why have you never heard of Shinder’s?

“I don’t know that people realize it, but this was the number one collectibles chain ever in the country” Steve Brown says. “Ever. Name another one. I can’t imagine anyone who reached those heights.”

If you’re from the Twin Cities of St. Paul and Minneapolis, you probably have Shinder’s in your DNA.

“If a kid was collecting something, he probably got it there,” says Tony Meinz. “It was part of so many childhoods. And it was famous. Every musician who played First Avenue went there. Jay Leno would talk about it on The Tonight Show.”

Brown and Meinz are former employees. Brown started at Shinder’s in 1987 at age 19, and miraculously was made a vice-president by age 20. He left before everything burned down, and started his own store, Cedar Cliff Collectibles, in 2002.

Meinz was hired by Brown in 1991 to work in Shinder’s warehouse. He eventually became warehouse manager, and later a senior buyer for the chain. He stayed until 2006, almost until the last dog was hung.

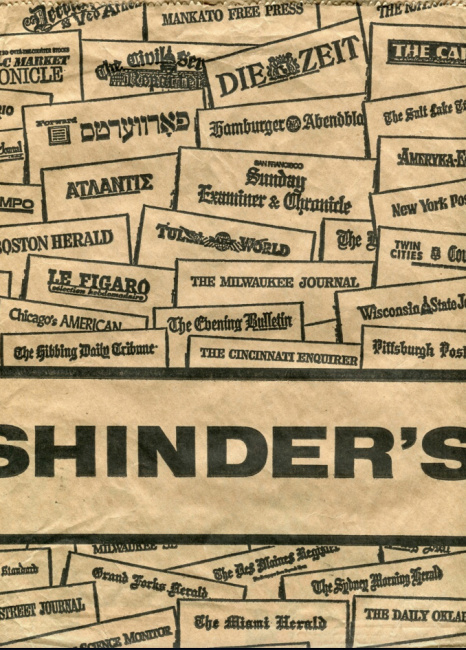

Shinder’s was a strange hybrid, with an origin story every bit as charming as its end was tragic. Three immigrant Shinder Brothers set up a newsstand on Hennepin Avenue in the heart of downtown Minneapolis in 1916. They soon had two newsstands bookending Hennepin at 6th St. and 7th St. They had immigrant hustle, and offered curbside service. “Rain, sun, snow or sleet, there’s a Shinder on the street” was their early slogan.

But brothers don’t always get along. The ownership structure was fractured, and the 6th St. and 7th St. stores were more competitive than they were cooperative. Regardless, one brother opened a store in downtown St. Paul, and three outlets now carried the Shinder’s banner.

Shinder’s offered a massive selection of magazines numbering in the thousands (many of the “sophisticate” variety, look it up, kid), books, and even Sunday newspapers from 50 or so locations across the world. Comic books were part of the mix, and when comics became a big collectible in the early ’70s, Shinder’s started specializing in back issue comics. [Note: The magazine term “sophisticate” apparently passed out of usage before the Internet; it was the trade term for magazines with nudity, which were among the newsstand bestsellers: Playboy, Penthouse, Hustler, Playgirl, Blueboy, and dozens more. – ed.]

By 1976, the old Shinder Bros. were getting very old, and a new generation stepped in. Joel Shinder, the son of one of the original brothers, bought out his various relatives, putting the stores into a single corporate entity. He also made two key moves.

One was a ’port to the suburbs. A tobacconist with a small news business in Minneapolis-adjacent Edina was looking to close up, and Shinder’s took over the location. Shinder’s set up shop in Edina’s Leisure Lane shopping center in 1976. Comics and a cornucopia of magazines (including the sophisticates) had penetrated suburbia.

The second move was perhaps even more important: Joel Shinder brought in Steve Kupetz as a business partner. Kupetz had a background in selling Asian rugs, and believe it or not, the buy/sell nature of the rug market mapped well to collectibles. Shinder’s was already known in the local market as a major comic dealer. By 1980 or so, when sports cards popped huge, Shinder’s got into that game, adding it as another collectible category with Kupetz at the helm.

Joel provided a topline vision to the new Shinder’s. Kupetz provided a 90-miles-an-hour drive and an iron hand.

“Joel was a nice enough guy. He was more detached. He was certainly involved in the business, but somehow seemed above it all,” says Greg Ketter of Dreamhaven Books, a Minneapolis books/comics staple since 1977. “He wasn’t the mover and shaker on a day-to-day basis. That was Kupetz. I had a few dealings with him. He had no regard for anyone. I didn’t like that guy.”

Steve Brown is more pointed in his analysis.

“Kupetz was an absolutely horrible human being in every way, shape, or form,” Brown says. “But man, he knew what the hell he was talking about. And he was stubborn; he would hit the same point 50 fucking times until you came around, right? And he was right about 99.9% of the time. He had the basic fundamentals of business down pat, and he didn’t care who got their feelings hurt or any of that. You had to have thick skin to deal with guy.”

Shinder and Kupetz were an interesting yin-yang. Joel had been educated at Harvard and Princeton, and held a Juris Doctor (basically a legal degree without taking a bar exam) and a Ph.D. in Middle Eastern Studies. He usually kept to his office, sparsely furnished and decorated by just one potted plant. Every now and then when Shinder’s would open a new suburban store and the Concerned Mothers would panic (those sophisticates!), he’d put on a sports jacket and talk to the papers about the First Amendment.

Kupetz was a bare-knuckles negotiator always shaving a nickel off any deal. He ran his day in staccato bursts, buttonholing Joel multiple times a day to grab coffee and a private conversation about the day’s business. He’d disappear multiple times as well to the Minneapolis Athletic Club around the corner where he’d play high-stakes backgammon games in the card room. He demanded pages of hand-written sales notes and observations from store managers and buyers. Once a week, Kupetz would devour the notes and connect the dots, “A Beautiful Mind”-style, to see which way the retail winds were blowing. He was almost always right.

More suburban stores opened. Shinder’s was booming. But Hennepin Avenue was diving. The street had long been ground zero for everything vice in Minneapolis, populated by mobbed-up business, strip joints, and seedy bars that dispensed both liquor and perhaps a few things a step or two up from booze. By 1987, the Minneapolis City Council had enough. The Shinder’s-bookended stretch of Hennepin had become the poster child for urban blight. The entire north side of the block between 6th and 7th was targeted for demolition. Shinder’s quickly moved to the south side of Hennepin and down to the corner of 8th, setting up shop in a former Burger King.

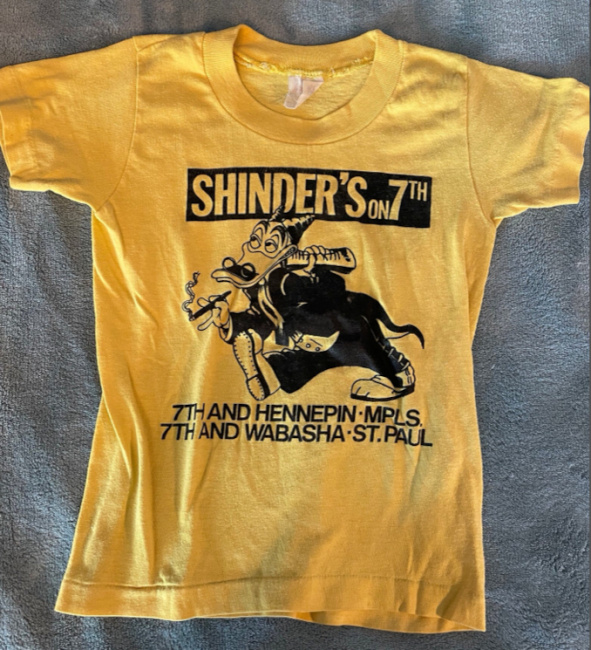

More suburban stores opened and a new downtown Minneapolis location was added just two blocks away on Nicollet Ave. (the fancy-people shopping district), and the chain grew to a massive 14 stores. The new 8th St. store maintained its primacy as the Shinder’s flagship. It was almost always open: 6:30 a.m. to 1:30 a.m., and populated by a staff that had to match a Hennepin Ave. clientele.

“We had punks working days bagging porn, and nights tackling drunks at First Ave.,” Tony Meinz says. “The place that would literally employ almost anyone. It was a true melting pot of culture.”

The attitude permeated into the suburbs. You could walk into a Shinder’s in a shopping mall called Cobblestone Court or Crystal Gallery and be greeted (or just as probably sneered at) by a register clerk blasting the Dead Kennedys or Public Enemy at max volume. But written into the equation was also a certain heart. If you were the weird kid, the goth kid, the strange kid, the D&D kid, Shinder’s was your second home. A manager at the suburban Burnsville store took a particular interest in role-playing games. He posted a dropbox where people would write a name, phone number, and games they played. He’d clean out the box once a week, dutifully record all the contact info in a notebook, and start making calls to connect gamers. Shinder’s was the proto-message board, the ur-WhatsApp.

And in the background… money, money, money rolled in. The Minnesota Twins won the World Series in 1987 and 1991, and sports card sales shot through the roof. By the time Shaquille O’Neal dragged basketball cards to the forefront in 1992, Shinder’s was Topps’ fourth-largest account: Only Walmart, Kmart, and Target sold more.

Shinder’s remained a juggernaut in comics as well. Longtime comic writer/artist Dan Jurgens had moved from rural Minnesota to Minneapolis in 1977 to go art school when a classmate first turned him on to Shinder’s.

“He took me downtown to the classic store on 7th and Hennepin and… I remember walking in and oh my God! All these comics! Back issues!,” Jurgens recalls. “It was amazing. It was my first experience in a store anything like that.”

As time went on and Jurgens became more attuned to the business end of comics, he learned of Shinder’s business acumen.

“I was told by distributors that the amount of comics being sold to Shinder’s to fill those 14 stores was massive,” he says. “I was told by Capital City about the amount of Death of Superman issues going into the Twin Cities, and it was astounding. And the bulk of them were going to Shinder’s.”

Capital City Distribution was Shinder’s distributor for comics. A time zone away, Diamond’s Steve Geppi craved it.

“Big account. I always coveted that account!” he says. “And they were a traditional bookstore chain as well. I coveted their volume, but also the ability to penetrate more a bookstore market as well. They were a great hybrid, and look what’s happened now: All bookstores are carrying comics, too. They were ahead of the game.”

Comics and sports cards boomed and busted throughout the 90s, and Shinder’s averaged $13 million a year in gross sales—the equivalent of about $25 million in 2023 dollars. No matter if it was POGs, Magic: The Gathering, Beanie Babies, Pokémon… Shinder’s would latch on to the latest trend, add it to the mix, and thrive, any competition be damned.

“All the other card shops, comic shops, the weekend warriors, they hated us,” Steve Brown says. “They hated us because of the massive economy we were doing. And we had zero shits to give as far as any of that went. It was a make-a-profit, bottom line operation, really run by Steve Kupetz. Idealism and capitalism do not mix. And at Shinder’s, there was no idealism. Only capitalism. Period.”

Eventually, Joel Shinder followed in the footsteps of his previous generation. He got older, and looking for a quieter life, he sold the business to Robert Weisberg, a distant cousin, in 2003. The highly prosperous chain took a 180-degree turn almost immediately, and started losing money fast.

Weisberg was a lawyer by trade, but had problems with his partners, and eventually got bounced out of the firm. His license to practice law was later suspended. His retail acumen proved no better.

“I became very suspicious of Weisberg’s smarts when he declined Kupetz’s help,” Tony Meinz says. “Kupetz said, ‘I’ll stick around one year and assist, help you with transition,’ and Weisberg said no. I thought, ‘Why would you not do that?’ I couldn’t fathom what kind of plan Weisberg would have that’s better than what Kupetz would have.”

“Weisberg violated the number one rule of nerd stores, which is ‘let the nerds run it,'” Steve Brown says. “He wanted Shinder’s to become a lifestyle brand store. He didn’t know anything. He was not beloved by anyone. None of his employees.”

Meinz saw the drift as well.

“Weisberg’s plan was just ‘bigger, better!’ But he was just a talker,” he says. “Nothing ever materialized that was bigger or better. He wanted to turn it into a superstore, like Target. Then he’d go to HOM Furniture and say, ‘We have to make the stores look like HOM Furniture!'”

Shinder, Kupetz and Brown were all key pieces, now missing. Sales dropped, stores started closing, inventory went missing. Shinder’s stated spiraling, and Weisberg spiraled even faster. In 2006, Weisberg’s van was pulled over by a multi-jurisdictional drug task force, and police found meth, Ecstasy, needles, a submachine gun, a police scanner, collapsible nightsticks, a digital scale, and more in the vehicle. Weisberg was arrested on drug charges. The decline hastened.

“The store closures were the worst,” Tony Meinz says. “You’d hear this location hadn’t paid rent in months, and a court date was set. Then Weisberg would do what he always did in court, which is show up late. He’d be, ‘What? 11 o’clock? I thought it was 1 o’clock.’ And they answer would be, ‘Yup. You lost your case.’ And suddenly that store is closing. You started just hoping rent was getting paid and your paycheck would clear.”

Dan Jurgens saw it as well.

“It was sad. It was very public,” he says. “At that point Shinder’s was a place my kids were shopping to buy Pokémon cards, sports cards, McFarlane figures, all that. Things started to come apart, a few stores would close, and by that time, you had gotten to know the staff on a first-name basis. And when you see them stressed out at their job, and next month they’re not even there… I don’t care about business at that point. That’s personal, and something you don’t want to see happen to anybody.”

Suppliers went unpaid, and supplies dried up.

“They were a comic store that wasn’t getting new weekly comics in,” Meinz says. “There was no new baseball card product, and it was baseball season. It was embarrassing.”

Meinz hit the wall one day in 2006 when he got a call from one of the chain’s newly minted VPs.

“He said, ‘Tony, can you call up customers and have them bring in cash?’ They wanted to get as much cash as possible to pay employees, and then everyone was walking out. So I called customers I knew, and was blowing stuff out. A 5,000-count box of vintage cards? I don’t care, make me an offer, pay in cash. Employees were just taking things off the shelves, no one cared, no one was sure if they were going to get paid.”

Meinz made his last walk—literally—that night.

“I had a company van, a company phone,” he recalls. “I just parked the vehicle in the lot, left the keys at the warehouse, and walked home. I knew it was over. I got calls on my phone from Weisberg over and over on the walk home. I didn’t answer. Fuck that. He was either going to try to threaten me, or get me to go back to work. And I wasn’t going back. There was no reason to be there.”

By 2007, venerable Shinder’s, aged 91 years, was dead. It was bankrupt, its assets liquidated.

A former employee, Larry Powley, tried revitalizing the old magic with a similar product mix and even some of the same locations, calling his stores “Beyond Shinder’s” in 2008. Those stores quickly closed.

All that’s left today is the name, the legacy, and a few assorted players scattered to the winds. Tony Meinz went into the medical field. Steve Brown has his store in suburban Eagan, MN. Joel Shinder is retired, and doesn’t talk about the old days.

Steve Kupetz is a minor mystery. He helped establish a co-op grocery store in Minneapolis after leaving Shinder’s. He made frequent trips to Asia, learning to speak Chinese with self-taught lessons on tape for four hours a day. It’s rumored he was hired by the government of Thailand a few years ago to help revitalize its economy.

Tony Meinz thinks Shinder and Kupetz getting out when they did was their final masterstroke.

“Those guys had impeccable timing in when they left,” he says. “LeBron James, 2003, got that benefit. Even Barnes and Noble was closing stores. Joel had his eye on eBay, thought that was the writing on the wall, eliminating the middleman. They got out at the right time.”

“It is one of the most amazing, untold stories in Minneapolis/St. Paul history,” Steve Brown says. “We had it all. Every store had giant cases with $100,000 worth of product in it, for sale, every time you walked into the place. We had a finely oiled machine. A warehouse, drivers going out every day. But the world is so young now. Those who remember it remember fondly.”

Brown also has one last piece of Shinder’s at his store, still paying dividends 16 years later.

“I still have Mylars from Shinder’s,” he says. “My God, I think I bought a whole skid at closeout.”

This article is part of ICv2’s Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary celebration; for more, see “Comics Direct Market 50th Anniversary.”

Source: ICV2