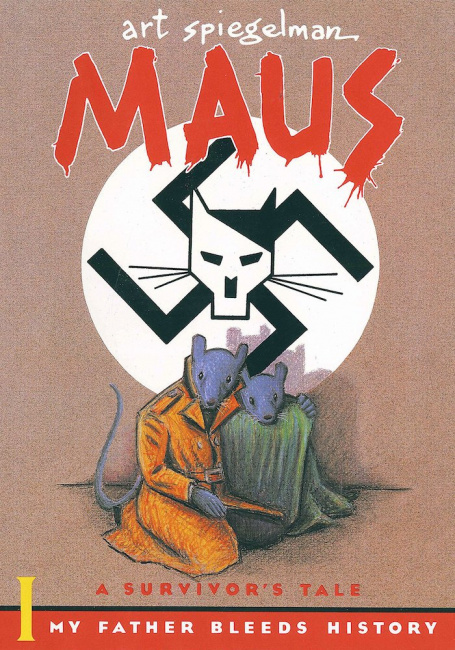

Last week in the wake of a Tennessee school board’s ill-conceived effort to remove Art Spiegelman’s award-winning Maus from its eighth-grade language arts curriculum over some objections to naughty language and drawings of naked mouse-people (see “Tennessee School Board Pulls ‘Maus’ From 8th Grade History Classes“), I interviewed CBLDF Executive Director Jeff Trexler over on Forbes. Jeff had a lot to say and it’s worth reading his – and CBLDF’s – reaction in full, but I wanted to expand on a couple of points of direct relevance to comic makers and retailers.

When censors come, comics will always be targeted. One point that Trexler raised in the interview is that comics occupy a unique place in the imagination of censors because of their properties as a medium that combines words and pictures.

As he said, “[censors] see images as particularly dangerous, and when you use the ‘bad words’ in combination with pictures, it’s somehow much more objectionable to them than seeing it in plain print. When they discuss bad language, violence, nudity in Maus, they don’t just say it’s problematic in itself. They see it as promoting suicidal ideation, violence. They see representation as making it real. It’s a serious misreading of how comics actually work. It’s a pre-21st century way of reading images.”

That’s one way to look at it. The other is that the pictures are a lightning rod for people who can’t be bothered to read a lot of words, much less parse out the creators’ larger intentions. When they can just flip through a book and pick out, say, a nude mouse, notwithstanding its role in the storytelling, they can display it in a light that is more objectionable and disturbing than it is in context. People react to the single image – which, as Trexler notes, is not how comics work – and stampede immediately to the conclusion that this is so sick and wrong that no one should get to read the work it appeared in.

Ironically, censors are not wrong to be worried. As any UX (user experience) designer or evolutionary biologist will tell you, we’re visual creatures and our brain interprets and acts on visual information hundreds of times faster than text, sometimes creating deep emotional associations instantly. There’s also something about hand-drawn images that’s even more compelling than photographs or video. All the stuff that Scott McCloud once explained to us made comics powerful make comics, you know, powerful: perhaps even more powerful and persuasive than finger-wagging censors, teachers, or, heaven forbid, parents!

This is only the beginning. This morning in Slate, Aymann Ismail interviewed author and professor Emily Knox about the motivations of the current wave of censors and she had this to say: “People are trying to get books like Maus banned because they are afraid that if their children read them, they will have different values than the values their parents want them to have. That’s really what this is about. People are looking at books as dangerous knowledge.”

Individual acts of censorship are worrisome enough, but it becomes a huge problem when censorship is systematic and coordinated. Right now we are in the midst of a full-blown moral panic about how white children in America are educated in public schools, fueled by a lot of guilt and anger, and supported by a lot of money. As Trexler said in our interview, “it was clear [from the 2021 Virginia elections] we’d be dealing with a wave of this in 22, 24, 26. It’s a viable wedge issue that crosses demographics and ideology, including on the left.”

That last point is important. Before we condemn the obvious issues at play in Tennessee, we should take note that on the same day, the Mukilteo School Board in Washington state voted to remove To Kill A Mockingbird from its ninth grade curriculum for Harper Lee’s quaint and deeply unfashionable midcentury approach to racial themes, which we enlightened folks today recognize as evidence of “white saviorhood.”

The bottom line is that the urge to censor comes from the belief that your side owns the truth and anyone who disagrees is a dangerous liar. It’s not enough to argue and persuade. You need the other person to just shut up because what they have to say is not a legitimate contribution to the discourse, and the last thing we could possibly do is trust readers to make up their own minds.

The odious practice of censorship always feels more compelling and necessary when “those other folks” are doing it and “we’re” just responding in kind to defend our right and true beliefs. Clearly we’re locked into this spiral right now, which suggests things will get worse before they get better.

So what can we do? For the time being, American courts and legal precedent provide some relief from the most ham-fisted attempts at censorship, although the issue of what educators can include or exclude from the curriculum is much more of a gray area. Trexler advises those who cherish free speech to grab the megaphone away from the scolds and censors: in essence, to normalize tolerance and stigmatize people whose first urge is to ban a work or banish a creator they disagree with.

That responsibility should start with those of us in the business, whether we are retailers, librarians, publishers, creators or influencers. After all, if we don’t care for or respect our readers, who will?

It also points to another uncomfortable truth: that organizations like the CBLDF remain essential, no matter how imperfect they can sometimes be in their operation, and no matter how often they confound us by siding with the “wrong” people on points of principle once in a while.

Look around. Stuff is on fire right now. This is not fine. And it is absolutely the wrong time to make the perfect the enemy of the good.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.

Rob Salkowitz (@robsalk) is the author of Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture.

Source: ICV2